Yesterday, I came across a brilliant exchange between authors Olivia Laing and Jamaica Kincaid about gardens.

“I think people want the garden sometimes to be a haven from history, a place to retreat, a present-moment feast of blooms. But of course, the garden is actually an archive, every plant bringing with it a narrative of past injustice, upheavals, shifts in wealth and taste,” Laing wrote.

Kincaid agreed. “It seems an act of willful thinking to believe that the garden would relieve us of the world we have created.”

Their words struck home because I’ve been wrestling with this post about the Japanese Tea Garden, a place whose history is tragic illustration of the limits to which a garden can shelter us from the world that we create.

The Tea Garden originated as one of the exhibits in the 1894 California Midwinter Fair – an extravaganza dreamt up by Chronicle publisher Michael DeYoung as a way to boost the city’s slumping economy and which for seven months sprawled across what is now the Music Concourse. (More to come on the Fair in another post.) The “Japanese Village” was built by an Australian named George Turner Marsh, one of the city’s earliest dealers in Japanese art.

Marsh hired a Japanese artist to design the exhibit, which included a theater, an artist’s studio, a tea house and a building that was billed as a “Japanese nobleman’s” home. He brought in Japanese landscapers to fill the grounds with trees, ponds and a waterfall, bridges, paths and lanterns. The main entry gate came from his own home in Mill Valley.

Marsh had lived in Japan and was fairly steeped in Japanese culture and art. Still, it rankled the local Japanese community and the Japanese government that someone who wasn’t Japanese was running the concession, according to an account by art historian Kendall H.Brown. They were especially offended by Marsh’s plan to ferry fair-goers around in rickshaws pulled by Japanese men; traditionally oxen did that job. Marsh’s response to the protests was to have German men in yellow face and traditional Japanese garb pull the rickshaws instead.

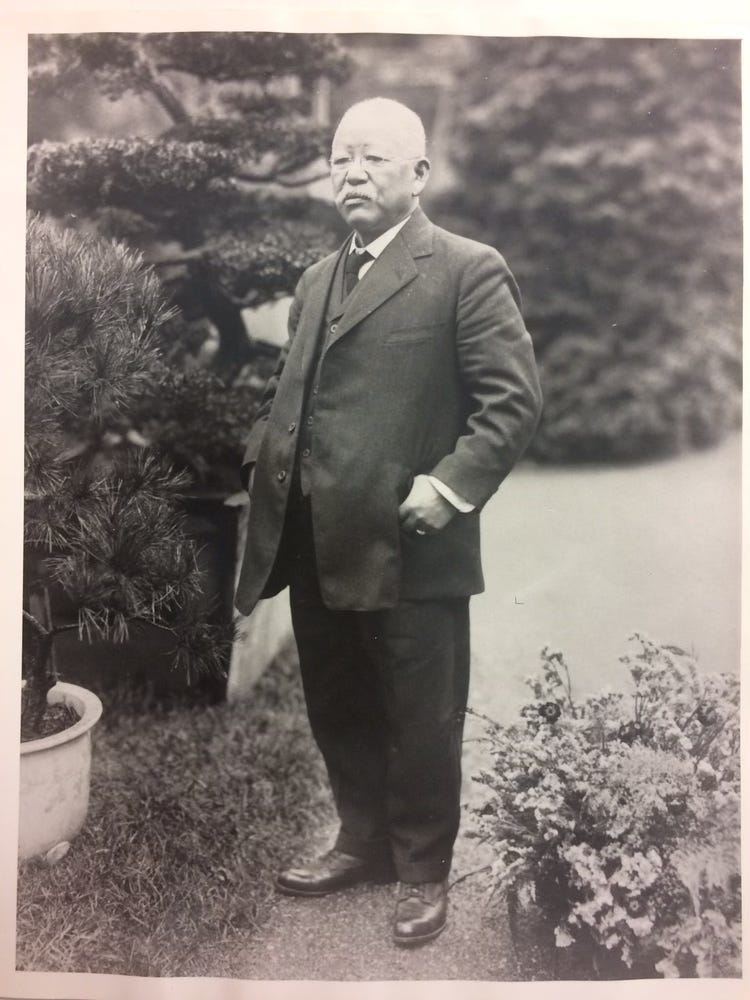

The exhibit was wildly popular and continued to draw visitors even after the fair closed in July, 1894. Rather than tear it down, Turner sold it to the city for $4,500 and hired a gardener named Makoto Hagiwara to be its caretaker and help oversee its renovation from a temporary exhibit to permanent garden. Hagiwara and his wife Tai moved into the second floor of the Nobleman’s house – above the gift shop — and stayed on after the Park Department hired Makoto to continue managing the space.

The Japanese Tea Garden, as it came to be known, would be home for four generations of the Hagiwara family.

Hagiwara, who grew up in a village in northern Kai province, was an early immigrant to San Francisco. When he arrived in 1878 at the age of 24, there were few Japanese in the city; the 1880 census counted only 86 Japanese in the entire state. He’d been a successful businessman in Japan, overseeing a silk production business and in this country ran a restaurant before opening a gardening business. But he was barred by racist federal immigration laws from becoming a citizen.

Working with park superintendent John McLaren, Hagiwara slowly developed the Tea Garden. He added ponds and koi, planted cherry trees and quince, and expanded the gardens. The family too expanded as Hagiwara brought over his two adopted daughters from Japan, Sado and Koto.

San Franciscans loved the Tea Garden for both its beauty and exoticism, for the glimpse it offered of “old Japan,” as newspapers at the time put it. But that appreciation couldn’t protect the family from the rising wave of nativism. In 1900, at the urging of Major James Phelan, who would later run for Senate on the slogan “Keep California White,” the city charter was amended to bar anyone ineligible for citizenship from working for the city. Hagiwara lost his job and the family was evicted from the Garden.

Hagiwara protested in a plaintive letter to the Board of Park Commissioners: “I challenge any Japanese or White Man to compete with me in my work. All my earnings at the park have been invested in beautifying and improving the Tea Garden. I have at my own expense imported from Japan many rare trees and plants. I extended the Tea Garden more than one half of its original size … I have drawn up plans for the future improvement of the garden and want to be given a chance to carry this out. I appeal to you to permit me to retain my position.”

The Board was unmoved.

So Hagiwara moved to a spot across the street on Lincoln Ave. where he set up his own competing Japanese Village. “It was his way of thumbing his nose at the city,” says Steven Pitsenbarger, now the Garden’s supervising gardener.

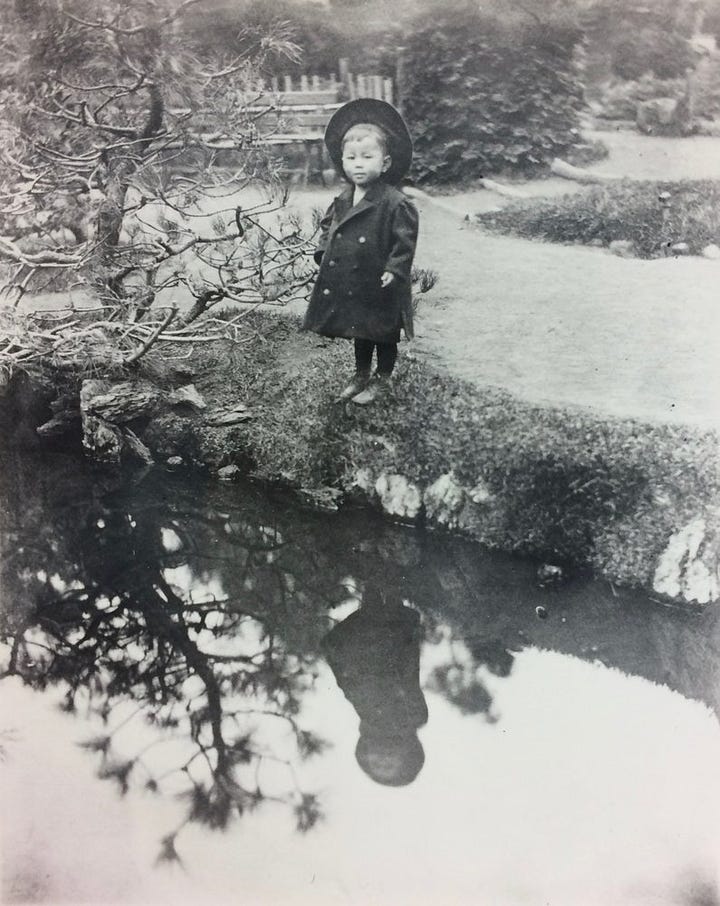

After the 1906 earthquake, with thousands of San Franciscans living in the park and the Tea Garden in disarray, McLaren persuaded the Park Commission to let him rehire Hagiwara. A few years later, the whole family moved back into the Garden, into a house Hagiwara had built. Set in the back behind the tea house, it held 17 rooms to accommodate the growing family. By then Hagiwara’s daughter from his first marriage, Takano, had arrived in the US, along with her husband Goro. They would have four children of their own: Sumi, George, Shigeo and Haruko.

Hagiwara continued to develop the Garden. He brought plants from Japan, installed a Shinto Shrine and later, a pagoda and temple gate that were displayed in the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exhibition.

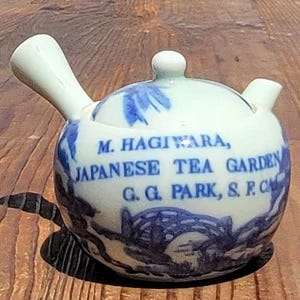

The family also ran the teahouse, serving green tea and cookies, including a confection Hagiwara created: the fortune cookie. It was a play on a traditional Japanese cracker, sweetened to American taste.

At first, the snacks were all they were allowed to sell. In 1908, they got permission to also sell small souvenirs, such as tea pots, cups and napkins to augment their income. All were stamped with the Hagiwara name.

Makoto passed away in 1925 and management of the garden fell to his son-in-law Goro. After Goro died in 1935, his wife Tanako took over.

By this time, the Garden was entrenched as a jewel of the city, beloved by a wide cross section. It was a destination for Bay area garden clubs; a luncheon spot for society groups such as the Cosmopolitan Club and the Daughters of California Pioneers. The Buddhist Mission of North America held birthday celebrations for Buddha there. Japanese dignitaries stopped in. And, of course, thousands of city residents would while away a weekend afternoon strolling the winding paths and oohing and aahing over the bowers of pink and white blossoms during cherry blossom season.

“If I had a million,” San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen wrote on Nov 21, 1941, “I’d spend at least 10 minutes a day in the Japanese Tea Garden in Golden Gate Park, still another world in the heart of John McLaren’s other world.”

Scarcely two weeks later, Pearl Harbor was bombed and World War II crashed in on the world the Hagiwaras had created. On Feb. 19, 1942, FDR signed Executive Order 9066, the infamous measure that forced about 120,000 people of Japanese descent into internment camps.

Once again, the Hagiwaras were expelled from the Garden – this time for good.

Almost immediately, the city began debating what to do with the Tea Garden. One man petitioned the Parks Commission to let him turn it into “a super deluxe hamburger and hot-dog lay-out.” He reportedly promised to get rid of all the Japanese statuary and “install a big statue of president Roosevelt.”

That set off a flurry of counter proposals and protests in the pages of the San Francisco Chronicle. One writer suggested turning it into a Chinese Tea Garden. Others suggested turning it into two gardens from both Asian traditions. One woman proposed having a series of various national gardens, “even of our enemies.”

But most people argued for the Tea Garden’s preservation. “Even though we were at war with the Japanese government, there was this subtle understanding that we were not completely at war with Japanese culture,” Pitsenbarger noted recently.

No one, however, protested the Hagiwara’s eviction. After negotiating with the city over what in the Garden was their’s, they packed up 32 truckloads of possessions and shipped it all to the home of a sympathetic landscape gardener in Mill Valley who had offered to store their things. In May, 1942, the family was sent to the Tanforan Assembly Camp and then to the Topaz War Relocation Center in Utah. “We had to leave behind three generations of hard work” as well as nearly $800,000 in property and possessions, Makoto’s grandson George Hagiwara would later testify.

The city quickly razed their house and removed everything reminiscent of Japan, such as the Shinto shrine. Chinese women replaced the Japanese servers in the tea house and the space itself was renamed the Oriental Garden.

When the Hagiwaras were released from the internment camp at the end of the war, they hoped to resume managing the concession. But the terms the city offered were prohibitive: a much higher rent -- $1,500 instead of $50-- and a 15 percent cut of earnings. There was no way back to the garden for the family.

They moved to Portland for a while and in the early 1950s returned to the Bay area, selling off some of their possessions from the Tea Garden to buy a home in the Richmond district. That included a prized collection of dwarf trees that ultimately wound up in the hands of a collector who years later donated them back to the Garden. George, who had spent his childhood helping his grandfather and then his parents in the Garden, got a job working as a cheese handler for Swift & Co.

After the US and Japan signed a peace agreement in 1951, the Park Commission changed the name back to the Japanese Tea Garden. But while the heritage was restored, the Hagiwaras remained largely erased. A plaque near the front gate, placed there in 1960 by the San Francisco Garden Club, honored George Turner Marsh as the Garden’s founder.

It would be more than two decades before Makoto Hagiwara got his due. In 1974, another plaque was installed on the other side of the entrance, this one designed by artist Ruth Asawa. Money for the plaque came not from the city, but from the Hagiwaras; they arranged to auction off several hundred teapots dating from the 19-teens that Makoto had bought for the tea house. Nearly 80 years on, the family was still giving to the Garden.

The unveiling took place on a drizzly March day when the cherry blossoms were all in bloom. Makoto’s grandson George, then 70, was there, as were two more generations of the family. A Chronicle reporter covering the event said George was quiet and had little to say except “it’s all past now but not forgotten.”

In 1983, the city agreed to pay reparations to the family. George and his sister Haruko were each given a payment of $5,000. Then-manager for Rec and Park Thomas Malloy told reporters, “This is the least we can do.” (Least is right!)

The family has continued to support the Tea Garden. In honor of its 100th anniversary in 1984, the family gave money to help fund restoration of the waterfall by the teahouse. And in 1986, Rec and Park renamed the road bordering the garden “Hagiwara Drive.”

The person tending the garden today, Pitsenbarger, is in touch with the family. He’s friends with George’s daughter Tanako, who was a small child when the family was interned at Topaz and is now in her 80s. “She's actually on our Friends of the Japanese Tea Garden group and always a pleasure to spend time with,” he says. “Like, if I'm being frustrated by the planning department or some other process, like, if I sit and have tea with her, I feel better.”

***

I’ve got another post on the Garden coming up in a few days. Part 2 focuses on the garden today and its longtime steward, Steven Pitsenbarger.

***

Sources for today’s post include:

Raymond Clary: The Making of Golden Gate Park, 1906-1950

Kendall H. Brown, “Rashomo: The Multiple Histories of the Japanese Tea Garden at Golden Gate Park, Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes, 18(2):93-119, 1998.

Steven Pitsenbarger, Japanese Tea Garden (This website designed for classrooms offers a great chronological account of the family with stunning photographs)

OutsideLands podcast on the Tea Garden, which features an interview with Pitsenbarger

San Francisco Chronicle

Thanks so much!

Great article. I learned so much!!!! I’ve always loved the tea garden.