Call and response

In the early years of Golden Gate Park, there were so few songbirds that the California State Floral Society in 1891 petitioned the park commission to import “feathered songsters.” I guess a new landscape is like a new restaurant or bar; it takes time for its patrons to find it.

The one bird that was abundant was the California quail. The park was being built on their native territory. And for a long time it remained a hospitable place for them, with ample lupines, sagebrush, coffeeberry bushes, blackberry brambles, bunch grasses and other plants the birds used for food, cover and nesting. With a population estimated at 1,500 birds, quail could be seen skittering all around the park. “From the benches one can watch the squads of plump hen‐like creatures as they move about with stately tread or stand talking sociably in low monosyllables,” ornithologist Florence Merriam Bailey wrote in 1902.

In those early decades, their life was cushy. They were fed every day by someone with the fantastic job title of “The Hermitkeeper. “Each morning he would come to the same spot and call them, presumably in their own tongue.,” writes Raymond Clary in his history of the park. “They would flock about the old man and scold him and ruffle their feathers until he scattered their breakfast of grain on the ground. A sentinel posted in a nearby tree would sound a warning if a dog approached. Then the quail would disappear in loud whirl of feathers and return only when the hermit sounded the all clear for them.”

Predators that had found their way into the new park found an easy target in the tame plump little birds. Coyotes, raptors, skunks and raccoons went after them. So did humans – for sport or dinner or both - though it was against the law. Clary tells the story of “a destitute but enterprising man” caught in 1891 while trying to nab quail with a slingshot for Thanksgiving dinner. He was fined $10, which seems mild compared to the month in jail another man got in 1933 for killing three quail.

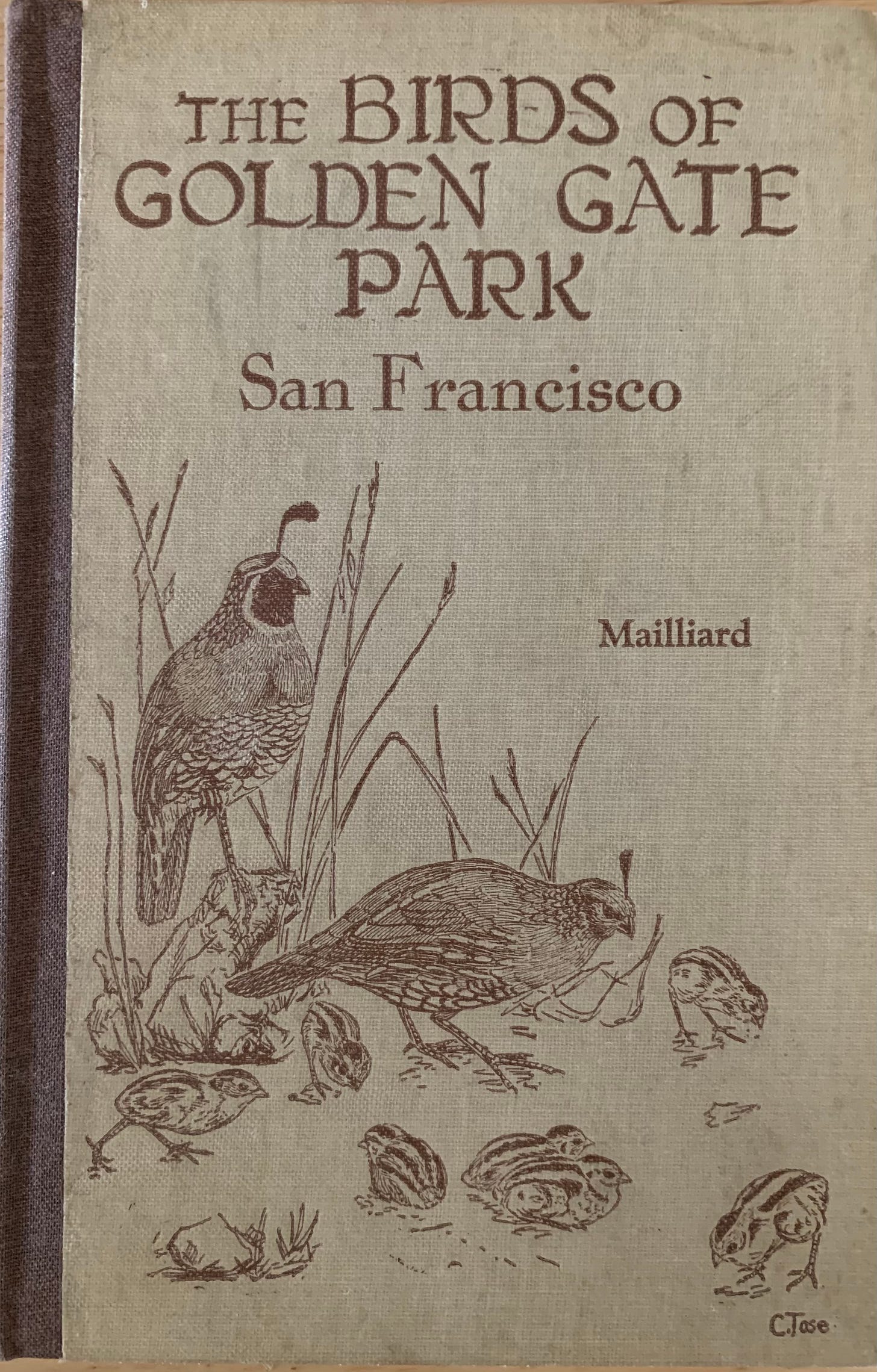

Quail were so abundant and so much associated with the park that Joseph Maillard put them on the cover of his classic 1930 book, “The Birds of Golden Gate Park.” He called them “one of the handsomest birds in California.”

Sadly, I don’t remember ever seeing quail in the park. I moved here in 1988 and wasn’t paying all that much attention to the park’s wildlife. But even if I had been, by then loss of habitat had dramatically dwindled their numbers— in the park, as well as their other haunts in the city, such as the Presidio and McLaren Park. More than a hundred years in, Golden Gate Park was now full of paved roads and cars, mature tall trees, ornamental gardens, lawns and non-native grasses. Quail need bare ground, plants with seed or berries and shrubby cover. Patches of this kind of habitation were now few and far between.

But the coup de gras may have been feral cats. In 1989 the SPCA adopted a no-kill policy. Stray were being neutered or spayed and released rather than euthanized. The population of cats in the park exploded. “That’s when the quail took a dive,” says Alan Hopkins, a longtime birder and former president of the Golden Gate Audubon Society, who helped mobilize a campaign in the mid-1990s called “Save the Quail.” He talked with me about the quail’s demise when we recently spent a few hours on a birdwalk in the park.

As so often happens in San Francisco, the issue became politicized. Battle lines soon formed between the bird people anxious to protect the quail and the cat people anxious about to protect the free-living felines. It was “a big war,” recalled Hopkins.

He and fellow campaigners did population surveys to track the birds’ waning numbers. They tried restoring quail-friendly vegetation in existing quail locales and finding new possible habitats. For various reasons, none of the efforts worked. For instance, a plan to create a place for the birds in Harding Park failed because it was too wet and…well, it’s a golf course, not a park. “We’d plant a bunch of plants and come back to find park staff had mowed them all down.”

Most of the efforts were concentrated in the Presidio. Hopkins said the administration there was more responsive to establishing quail-friendly habitat than was Rec and Park. But habitat takes time to grow and the birds’ numbers were dropping fast. By the time the quail was named San Francisco’s official bird in 2000, there were only a dozen left in the city.

The number in Golden Gate Park eventually dwindled to just three: two males that had been in the Presidio and somehow found their way to a lone female in the Botanical Garden. The trio managed to produce a few offspring for a few years, but by 2017, only a lone male was left. Birdwatchers called him Ishi — a name that has become an emblem of extinction.

The original Ishi was a native American who was the last surviving member of the Yahi people. His tribe had been decimated by disease, starvation, and slaughter by white settlers. After years of hiding in the foothills of Mount Lassen, the man stumbled into Oroville one day in 1911. Intrigued by news reports about the “last wild Indian”, University of California anthropologist Alfred Kroeber arranged for the man to be brought down to him in San Francisco. The man would not reveal his name. That was taboo for a Yahi. So Kroeber decided to call him “Ishi,” an anglicization of the Yahi word for “man.”

For the next five years until his death in 1916, Ishi lived at the UC Museum of Anthropology in Parnassus Heights, just up the hill from Golden Gate Park. He spent his days (who knows how voluntarily) working on the grounds, making arrow heads and demonstrating other Yahi traditions to visitors, while also being studied by Kroeber and other scientists. (I’m reluctant to try to condense their complex relationship to a few sentences. Douglas Cazaux Jackman explores it in his fascinating book “Wild Men: Ishi and Kroeber in the Wilderness of Modern America.) In his free time, according to Jackman, Ishi often took walks in the park, where he befriended the staff. Park superintendent John McLaren gave him a plaid shirt. The aviary keeper gave him feathers for his arrows. A gardener gave him “slips of roses and fuchsia,” which he in turn gave away as gifts. As Ishi wandered, taking in the park’s many sights, he undoubtedly encountered quail.

Ishi the quail spent his time among the bunch grasses in the native plants section of the Botanical Gardens and in the bushes near the Handball Courts. People would hear him calling “cu-ca-cow, cu-ca-cow,” the call of a bachelor bird seeking a mate. Birders were haunted by the spectacle. Quail are gregarious animals. They live in communities of dozens of birds where they’re forever chattering with another. Such profound aloneness seemed an unbearably cruel fate for such a sociable animal.

Ishi was last seen sometime in the spring or summer of 2018. After that, there were no more sightings or calls.

After having fought so hard to prevent the bird’s disappearance, Hopkins felt moved to address it through art. (He studied painting at the San Francisco Art Institute; “another extinction,” he said wryly, referring to the school’s closure last year.) In 2018, he began working on a series of mixed medium paintings he titled “Calls with No Response.”

The paintings don’t reproduce well in photographs because they are mostly black with a subtle surface texture. But here’s how Hopkins described them: Most of the pieces are composed around a pair of rectangles. “I'm sort of playing off whether or not the rectangles can find each other, hear each other. There's kind of a little gap between them.” The rectangles are deliberately hard to see so the viewer has to work to find them. “My thought is it's not just about quail, but it's about all the species where there's one animal left and it can't find a mate.”

(He’s showing those works at the Shipyard Open Studios, Oct. 21-22. He’s in Building 104, Studio 1103.)

That’s not quite the end of the quail story though. Two quail were detected in the city this year: one in the Presidio, another near Lake Merced. Hopkins doubted either of of wild origin.

Meanwhile, a 2021 study suggests restoring quail in the city parks might be more successful now than it was in the past. The surprising reason: coyotes. The study found that the presence of coyotes in California urban parks increased the likelihood that quail were also there by an astonishing 73 percent.

“Coyotes create top-down control,” Lew Stringer, associate director of natural resources at the Presidio Trust, explained to journalist Tom Molanphy. “They eat rats, raccoons, feral cats, and open up the ability for quail to exist.”

The coyotes are creating an opportunity. The next step is establishing connected, good-sized areas of quail-friendly habitat in the Presidio and the park where the birds can safely be reintroduced. Nature is offering a call; now it’s our turn to respond.

Postscript: Steve Kane, who took the photo of the nesting quail above told me that there was, and maybe still is a bench featuring quail in what is now the Celebration Garden in the Botanical Garden. He shared a photo of that bench taken in 2011:

You can find Steve’s work at www.smkanephotos.com.

Thank you Laurel -- you're so lucky! I've rarely seen them in action.

Thank you for this story, and I appreciated the Ishi connection. We loved hearing and seeing the park quail, mostly in the (then) Strybing Arboretum. I did a quick search of my photo files, and the last images I have of the quail date to 2010. There used to be -- perhaps still is? -- a wood bench in the Botanical Garden with lovely quail carvings.