When you settle onto a bench in Golden Gate Park, there’s a good chance it will be one that carries a memorial plaque. There are about 500-600 of these commemorative benches scattered across the park, and hundreds more in other city parks.

These plaques transform a simple place to sit into something more. Each endows its bench with a history, animating it with a past life. As writer Edwin Heathcoate observed in a lovely essay on park benches, “when we park ourselves on a bench with a memorial plaque, we’re sitting with the ghosts of all the others who have sat there before us.”

Jim Jenkins found himself amongst the bench ghosts after the worst year of his life. His marriage had collapsed, he’d lost his job and was diagnosed with leukemia. Reeling from that epic crash and burn, he began visiting Golden Gate Park. He’d while away hours sitting on benches, sunk in his thoughts, “feeling sorry for myself.”

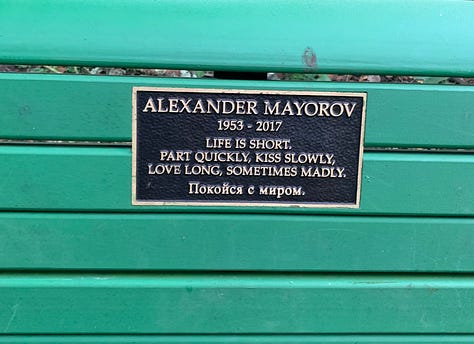

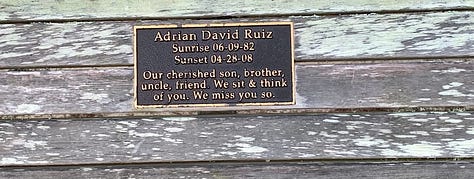

At some point he began to notice the embossed bronze memorial plaques. Some were sad, indicating a life cut short, others were witty, romantic, mysterious or simply sweet.

Some made him think about his life, and see it in a different light. Jenkins was nearing 60 and he’d see a plaque for someone who had died at a much younger age. He’d think to himself, “What are you so sad about Jim? Here's this person who only got a taste of life.”

He started wondering about the people behind the epitaphs. Who were they and who were the people holding them in memory? His questions, and the search for answers, helped pull him out of his funk. He’s now working on a book about the stories of some of those ghosts. As a local history buff, he sees in the small tales contained in the terse commemorative plaques strands of the city’s larger history. They’re like “joyous cemeteries,” he said. As someone who has always loved the stories to be found in old graveyards, I was excited when Jenkins agreed to share some of his discoveries with me.

Jenkins is tall and lanky, with shaggy greying hair and a disarming earnest openness. We talked at a coffee shop for a while where he readily shared his personal story. We then walked over to the park to see his favorite commemorative bench. It’s on Martin Luther King Drive, parallel to 5th Ave. and bears this somewhat cryptic legend:

Jenkins tracked down one family member, John Cuff, to learn the story behind it. Joseph and Terry Cuff and their five sons lived in a Victorian on 10th Ave., just a few hundred feet from the park. Joseph was a firefighter. In 1962, he was killed when his fire engine collided with a livestock truck. Terry went on to raise the boys by herself, but she wasn’t alone. She had the help of her tight-knit neighborhood, the local Catholic parish and Golden Gate Park. In a draft of his book, Jenkins describes how she and other neighborhood moms would shepherd a passel of kids across Lincoln Ave. and into the park to spend an afternoon:

Picnics were set up on the vast lawn of Sharon Meadow (now Robin Williams Meadow) and the kids were turned loose on a smorgasbord of fun, including the playground, a petting zoo, a carousel built in 1912, a concessions stand that sold pink popcorn and ice cream, and the ornate Sharon Building …. On the way home, the army of kids and moms would fill half a city block, and tourists would always stop them to ask directions to the playground, with its famous attractions. Hundreds of fingers and dozens of little arms would raise in unison and the children’s shrill voices would yell out, “That-a-way!”, pointing in the opposite direction from whence they came.”

Once the boys got older – meaning after fourth grade – they roamed all over the park on their own. To Jenkins, the Cuff’s story evokes a more innocent (perhaps mythical) San Francisco. A time when a couple could buy a house on a firefighter’s salary, when neighbors took care of each other and kids safely could have the run of the city. After Terry passed away in 2019, the sons, who all lived elsewhere, sold the family home. John Cuff told Jenkins he commissioned the plaque as a way to maintain “a spot in the neighborhood.”

Another plaque he’s researched took him into an unhappy chapter from the city’s labor history. Dow Wilson was a housepainter and activist in the Brotherhood of Painters, Decorators and Paperhangers. An outspoken advocate for union rank and file, Wilson went up against his union’s corrupt leadership. He was shot and killed after leaving a meeting at the Labor Temple one night in 1966. It was later revealed that a top-ranking official in the union had put out a contract on Wilson’s life.

Jenkins has been aided in his research by Paula Martin, the dedicated and genial overseer of the commemorative bench program at SF Parks Alliance, the non-profit partner of Rec and Park. Martin points out that few of the benches honor famous or prominent people. (There are exceptions, especially at the Music Concourse, one of the most requested spots by donors. That’s where you’ll find benches commemorating: generations of the DeYoung family; Alfred Wilsey, husband of DeYoung benefactor DeDe Wilsey; Kurt Herbert Adler, longtime conductor of the San Francisco Opera; concert promoter Shelley Lazar, among others.) Other popular spots are Stow Lake and the Queen Wilhelmina Tulip Garden. Says Martin, “I always tell people to look for places that are meaningful to you – where you walk your dog, where you walked with your grandma, the playground they took you to.”

Martin appreciates the ghost stories the benches contain. But what she loves most about them are the living connections to the park that they foster. “People who donate to have a plaque placed visit the park and keep an eye out. They take care [of their bench]; they report graffiti and garbage,” she said. Donating a bench in a loved one’s name “creates a sense of community and stewardship.”

—

If you’re interested in donating a bench, here’s what you need to know:

It costs $6,000 to donate a bench (unless you want one at the Palace of Fine Arts, in which case it’ll cost you $10,000.) The plaques are good for ten years, though many stay up far past their - ahem - expiration. The donation, a significant fund-raiser for the city parks is tax exempt. Thirty-five percent of each bench donation goes to the Parks Alliance to cover the program; 35 percent goes to Rec and Park’s general fund and 30 percent to Rec and Park to pay the cost of bench refurbishment and maintenance. For more information, contact, the San Francisco Parks Alliance.

And if you want to see commemorative benches all over the country, check out this open source map.

It really was a backyard playground to so many of us!