Gardening isn’t often a route to fame. As one of the park’s gardeners recently said to me, “you don't really see us.” And many of them, as well as many of us visitors, like it that way.

Still, we ought to know who to thank for this gift that’s been giving for 153 years. Sadly, the man who created Golden Gate Park has been buried in anonymity and unfairly overshadowed. So in honor of the park’s birthday this month, I want to celebrate William Hammond Hall.

Hall was a kid growing up in Stockton when in the 1860s, civic leaders began pushing to build the city’s first public park. Until then, the only public open spaces were a few small, grimy squares and plazas. They wanted to bring class, beauty and breathing space to their rough hustling boom town. The world’s great cities had great parks—why not San Francisco? They had in mind something on the order of Central Park – but to outdo New York, they’d make it nearly 200 acres bigger.

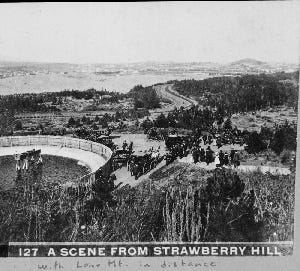

They couldn’t have picked a less promising site in which to plant their aspirations: a forbidding region on the city’s far western edges known as the Outside Lands. It was a vast barren expanse of drifting sand dunes, scoured by ocean winds, miles from anywhere anyone lived and near-impossible to reach. “During high winds, the flying sands would pelt the face of a man on horseback and it was sometimes difficult to make a saddle-horse face the wind,” Hall recalled.

The Original Outside Lands

In 1870, the newly-formed Board of Park Commissioners put out a call for the land to be surveyed. Hall, an Army-trained civil engineer, had spent time in the Outside Lands working with the Army Corps of Engineers. He submitted the lowest bid and won the job. Six months later, Hall parlayed that experience and political connections into getting hired as the park-to-be’s first Engineer and Superintendent. He was just 25 and wildly ambitious, but had no formal training or experience in park-making. And now he had to figure out how to build a verdant oasis atop this Sahara.

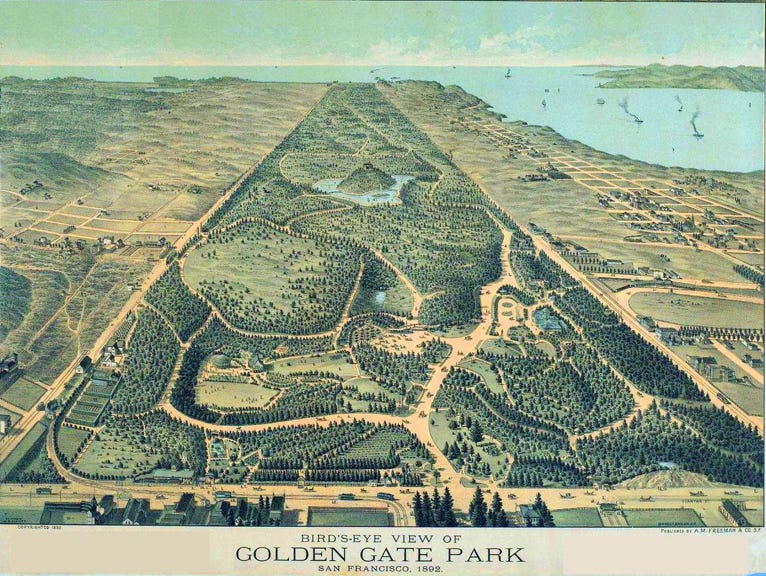

Hall had only a rough plan at first, but a clear vision. He aimed to create a woodland park — “a bit of country in the city” that would provide “relief from hard-line surroundings and disturbing city-like influence” for people of all classes. The one place in the city open to anyone of any means for rest and recreation. This park would have winding drives for carriages and rambling paths, grassy meadows and sparkling lakes, a children’s play area, fields for baseball and croquet, rustic pavilions where visitors could stop and take refreshment — and of course, scores of plants, and shrubs and trees.

Few others believed such a miracle was possible. Every newspaper treated the effort as folly, while powerbrokers who had hoped to site the park in other locations that could benefit them (like the Mission or the Presidio) continued to fight the plan. Central Park’s creator Frederick Law Olmsted had warned the park’s backers against building a park on arid sands.

Beyond the Sand

Hall, however, was able to see “beyond the sand,” Rec and Park historian Christopher Pollack writes in a wonderful essay about Hall. Through his survey work, Hall had gained a unique understanding of the Outside Lands’ geography, geology, hydrology and vegetation and the interplay between them all. He recognized how the landscape and climate were shaped by wind and fog. He knew there was water in places under the sand, as well as several small natural ponds and spots where lupine, grasses, shrubs, and even oak trees grew. He then embarked on a crash course of study to learn what he didn’t know – which was almost everything—about the mechanics of park-building, including seeking out Olmsted as a mentor.

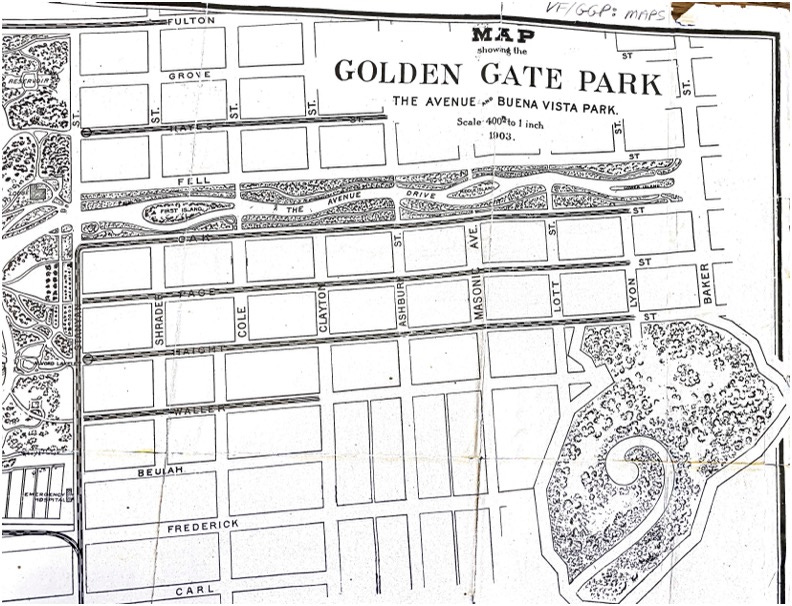

Hall started at the long narrow eastern end – today’s Panhandle, then called The Avenue —where his survey had revealed there was arable soil, abundant water and scrubby oak trees that could help anchor and protect any new plantings. It was a smart political move. An inviting entryway would help defuse detractors and encourage continued funding for the much more difficult task of transforming the remaining 800-plus acres of sand. Hall ignored the kibitzers who urged him to build straight roads along the stretch. The roads needed to be curving and sheltered by clumps of trees to protect visitors from winds blasting in from the ocean.

Barley Saves the Day

As the Avenue took shape, Hall began in 1872 experimenting with methods to still the restless dunes. From his work with the Army Corps, Hall had learned about techniques used in Europe to turn sandy coastlines into arable land. Grasses could be planted to anchor the sand, followed by a succession of other plants, shrubs and trees to build soil on top of the sand. One of the plants Hall planned to start with was lupine, a deep-rooted native of the dunes, but it didn’t grow fast enough to restrain the sand.

Luck solved the problem in Hall’s telling of the tale. (There’s another version which I’ll write about sometime later.) While camping out in the dunes, one of his horses spilled soaked barley seed from its feedbag. When Hall happened by a week later, he found the spot covered with green barley sprouts. Sowing the sand with barley and other grasses, would temporarily hold the sand while the lupine took root and grew. By 1873, writes Pollack, “the drifting sands at the beach had been tamed and further harnessed with a fence made of boards and posts covered with tree boughs and brush.” The fence extended the length of Ocean Beach and helped barricade the inrushing winds.

A Desert Blooms

By then, a real park was emerging from the once-barren landscape. By 1875, Hall had planted nearly 60,000 shrubs and trees—the Monterey pines, cypresses and eucalyptuses that he’d determined grew best on the site —and laid down a maze of twisting roads, and bridle paths and promenades. There were even a few rustic buildings. Some 600 people were visiting the park each weekday, 1,000 to 1,200 on Sundays. The city’s newspapers ran proud features about the new civic treasure. “The desert has been made to blossom as a rose,” one crowed. Olmsted eventually acknowledged that he’d been wrong and congratulated Hall on results he had not thought possible.

Blacklisted by a Blacksmith

Still Hall had made enemies, one being a blacksmith he’d fired for padding his bill by “more than 100 percent.” The blacksmith had vowed to get even and made good on the promise when he was elected to the state assembly. In 1878, he convened a special committee to investigate various alleged wrongdoings by Hall, including taking wood from the park for personal purposes. It was an absurd charge: Hall was so scrupulous in his devotion to the park, he once told one of his foremen to return kindling harvested in the park that had been delivered to his home. When the blacksmith’s allies in City Hall cut his salary in half, Hall resigned in disgust. He went back to engineering and became California’s first State Engineer.

In 1886 the Park Commission brought him back as a consultant. He served without pay for three years —long enough for him to help hire a new superintendent, a landscape gardener by the name of John McLaren, whose staggering 56-year tenure led to Hall’s eclipse. As Hall faded from the scene, growing numbers began crediting McLaren with being the mastermind behind the park.

Hall died in 1934 at the age of 88. He had long wanted to write a history of the park’s early years and actually wrote three. Never published, they all reside with his papers at Bancroft Library. The last, “The Romance of a Woodland Park” consists of 400-plus typed onion skin pages of Hall setting the record straight, claiming “very much gross error…has found its way into print.” While rich in detail, the pages boil with bitterness and frustration. He was infuriated over aspects of the park’s later development, and ways he felt city politicians had been careless with it or “misused (it) for class and personal aggrandizement.” He hated the museums, the short-lived Speedway, the decision to permit cars in the park, and the “dark decade” following his departure when the park was deliberately underfunded.

And he seethed over how often McLaren was given credit for the Park’s creation. (For instance: a 1930 San Francisco Chronicle described McLaren as “conqueror of sand dunes” and “the garden wizard who made Golden Gate Park over from a wasteland into a luxuriant playground.”) As Hall notes over and over, the park had been up and running for 16 years before McLaren became superintendent.

Leafing through the pages, I feel for Hall. It’s a terrible thing to feel your creation has been desecrated, to be overlooked and forgotten.

Though various people at different times have sought to give Hall the recognition he deserves, there is still no lasting monument — no road or meadow or statue honoring him. Rec and Park gives out an annual William Hammond Hall Award to worthy gardeners or horticulture professionals. Otherwise, the only tangible acknowledgment is a conference room named in his honor, tucked away on the second floor of Rec and Park headquarters in— yes! —McLaren Lodge.

What do you think should be done to give William Hammond Hall his due?

**

To learn know more about Hall, check out:

Raymond Clary, The Making of Golden Gate Park: early Years: 1865-1906

Terence Young, Building San Francisco’s Parks, 1850-1930

Christopher Pollock, “William Hammond Hall: Still the Unsung Father of Golden Gate Park”

I love the postcard image, which shows the true scope of GG Park. When you're walking in the park it feels so beautifully contained, it doesn't feel as huge as it really is!

It's amazing to see that 1865 photo of Outside Lands with only the Cliffhouse there. By the time I moved to the Outer Richmond, it looked the way it does now--houses as are as the eye can see. My father-in-law grew up there too.

Thank you for telling Hall's story--and the barley! How interesting!

Fascinating story —and a great tribute to Hammond. I’d never heard of him. And I doubt I’ll ever visit the park on a windy day without thinking of those poor horses!