I confess: until recently I never considered the panhandle as anything more than a pleasant stretch to bike through on my way to or from the park. I thought of it as a pass-through space. One SFgate writer called it the city’s “most underrated park” with “its long flat promenade style” and lack of views or interesting attractions. But while it feels like an afterthought of the park, in fact it’s a forethought — the first part of the Outside Lands to be transformed into park land.

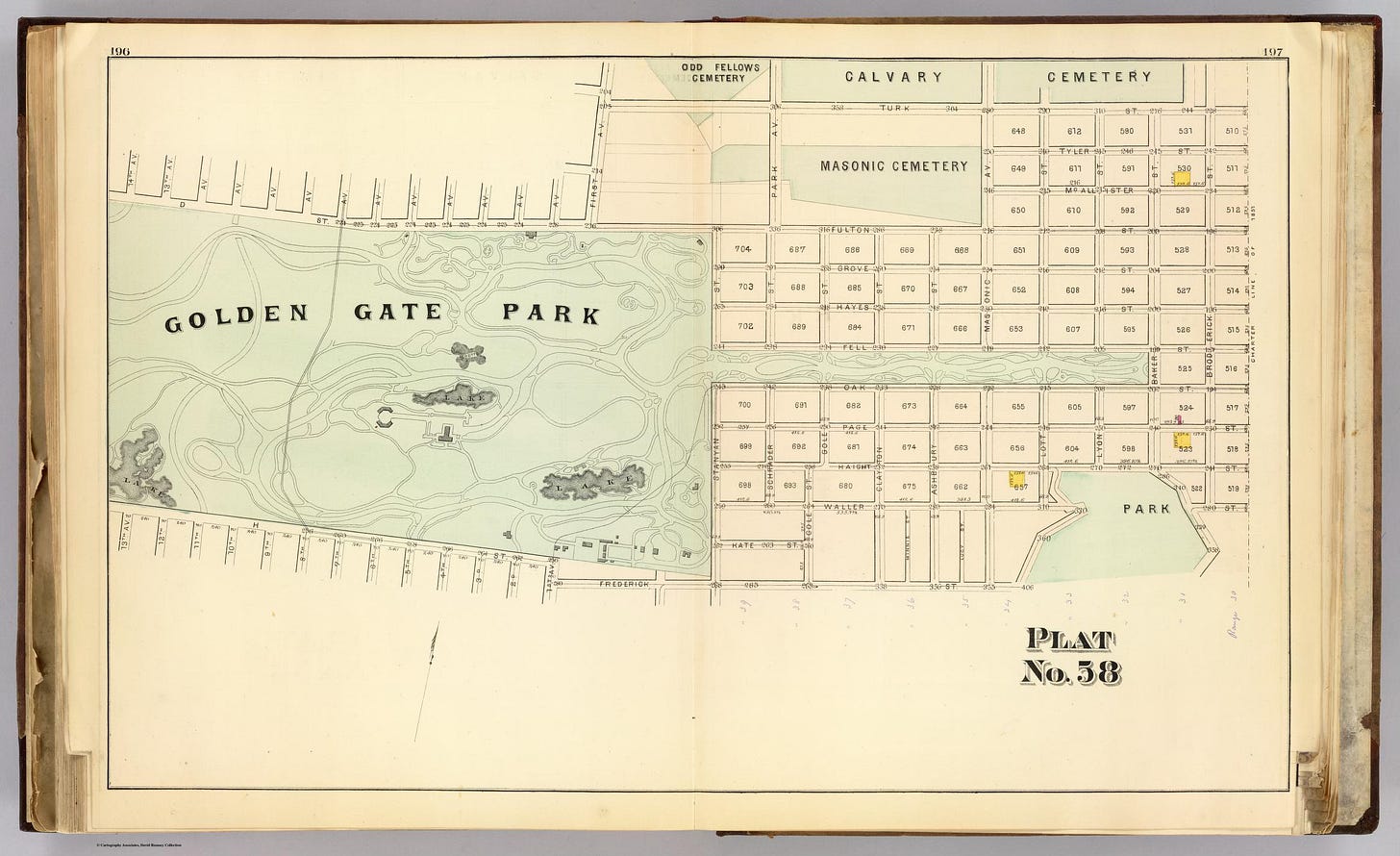

Originally Golden Gate Park was meant to be a solid rectangle, extending between Fulton and Frederick all the way down to Divisadero. According to former San Francisco Chronicle columnist Margot Patterson Doss, “a singularly tenacious group of squatters had settled in Hayes Valley. To claim any land is this area for the park, the city fathers had to compromise and the Panhandle is the result.” A strange green tongue sticking out into a mostly empty landscape, just 275 feet wide and 4,000 feet long.

William Hammond Hall called the strip “the Avenue reserve” and laid it out to serve as an inviting entryway to the main attraction. It was designed as a liminal space — a transitional zone from the hectic and hard-edged city to a rustic wooded “pleasure grounds”. A long road — the so-called Avenue —wound down the middle, at first carrying horses and carriages, and after 1913, cars.

Automobiles would shape the space over the next 40 years. First in 1922, when pressure for more cross-town routes led the city to continue Masonic across the panhandle, cutting the long strip in two. And second in 1955 when the central roadway was removed and the asphalt replaced with grass, refashioning it into an eight-block meadow. (Another time I’ll tell you about the bonkers plan to put an eight-lane freeway through the panhandle, which were finally quashed by a coalition of activists in 1964 — the so-called Freeway Revolt.)

With the road gone, trees came to dominate the space. The panhandle contains some of the oldest, grandest trees in Golden Gate Park. Some accounts claim Hall treated it as a test lab for trees and shrubs that might later be planted elsewhere in the park. I haven’t been able to determine if that’s true. But the soil was more fertile than the sandy land to the west, and in 1871 Hall began setting out different types of shrubs and trees, including the trio of species that are stalwarts throughout Golden Gate Park: Monterey cypress, Monterey pine and blue gum eucalyptus.

Eventually some 50 different species would be planted in the Panhandle, nearly all from other parts of California, other states, or from Australia, New Zealand, Europe, South America. The only one native to this area was a lone coast live oak.

In thinking about the panhandle, I’ve realized how wrong I was to write it off as just a pass-through space. For folks living to the north and south, it’s their neighborhood park. D’uh! “It’s my communal backyard,” said Guinevere, a musician who lives nearby on Lyon St. and likes to come to the panhandle on nice days to read and relax. On the day I met her, she was doing just that in a hammock strung between two pine trees.

But it also feels like more than a neighborhood park. Even with cars rushing by on either side and the steady stream of bike traffic and runners along the curving paths, there’s an essential calm to the space.

I wonder if that’s partly because there are few distractions — just a small playground, a little outdoor gym, and a basketball court that was built on a remnant of pavement from that former roadway. There are no picnic tables and the only “art” is the McKinley monument at the far east end. There are few ornamental plantings and no flower beds to speak of. Benches unobtrusively line the paths bordering the strip, leaving the middle area an open expanse overseen by towering trees — soaring eucalyptuses shedding their ribbons of grey-green bark and brooding corrugated pines and cypresses.

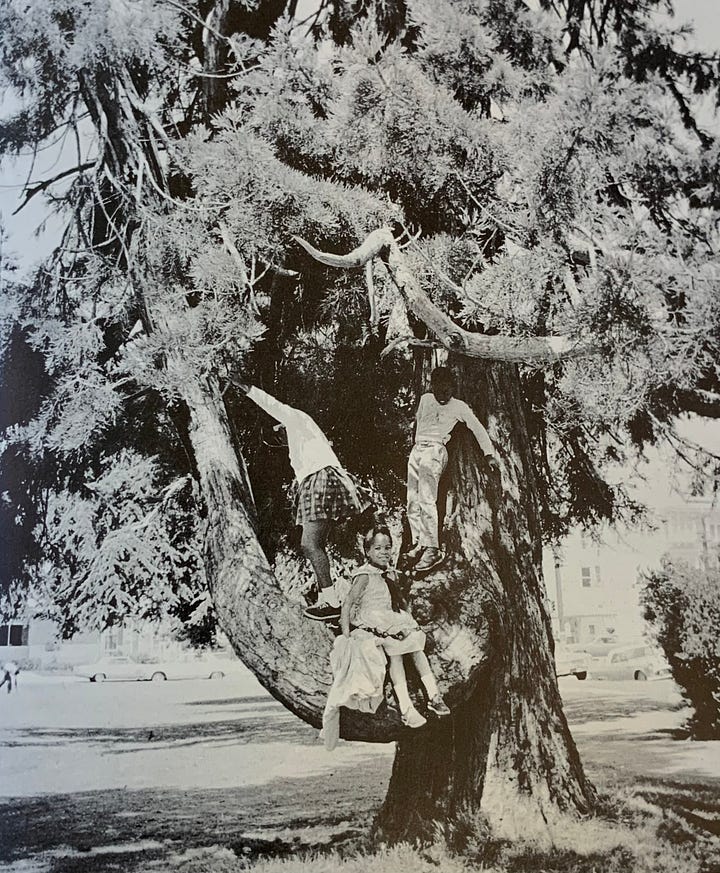

Many parts of Golden Gate Park contain extraordinary trees. (The redwood grove, for instance.) And yet the trees in the panhandle case a different kind of spell that permeates the space. Maybe it’s because they’re widely spaced, each stands out as an individual. The effect feels less like an urban forest and more like an arboreal museum, where you can appreciate each tree. Sit against the knuckled roots of one of the old eucalyptuses here, look up into the branches reaching high above and you can feel the presence of something solid, stoic and steady.

It’s hard to know which of these trees date to the panhandle’s earliest days. The mainstays — the eucalyptuses and Monterey pines and cypresses — have limited lifespans; no doubt many have died of old age or disease or been toppled by storms and replaced. Plus, over time horticultural fashions and preferences change.

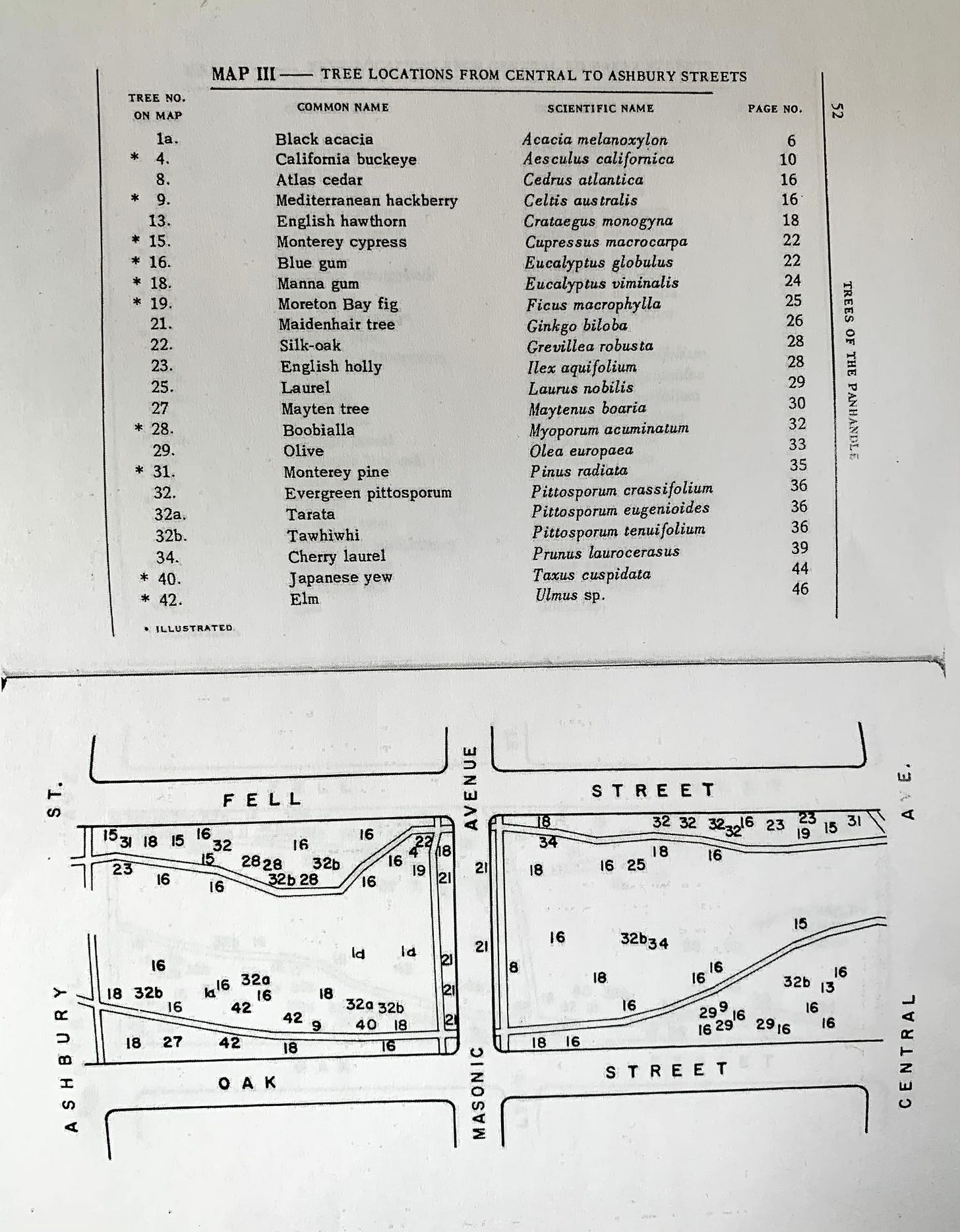

In 1965 Elizabeth McClintock, a botanist at the California Academy of Sciences, catalogued all the trees and shrubs then growing in the panhandle. The resulting book, matter-of-factly titled, “Trees of the Panhandle”, also contains maps showing each tree’s location. (See the bottom of this post for all four maps).

`

I walked through the panhandle the other day with the maps in hand hoping to get a sense of what was still there and what was gone. Trying to check the status of every tree would have taken days if not weeks, (and I’m not great at tree identification.) So I just picked a few trees to check up on.

I was hoping to see the Anchor plant – mainly because of its other name: the crucifixion thorn. McClintock described it as a “grotesque, spiny much-branched shrub “ that’s about 9 to 10 feet tall. There had been one just off Fell St., between Lyon and Central Avenue. Sadly not any more. But the lone coast live oak which I’m betting dates back to Hall’s time was still there.

I also wanted to see the boldo tree, a Chilean native. In McClintock’s day the one in the panhandle was the only one in the entire park. Indeed, she said, the only other known boldo in the Bay area was on the campus of UC Berkeley. I don’t know if the Berkeley tree remains, but the panhandle’s boldo is gone.

The six gingkos that once bordered both sides of Masonic were also no more —in fact, all but one was gone by the time the 1973 edition of her book came out. I couldn’t find the last one. Instead their place is now occupied by several tulip trees.

In 1965, there was just a single olive tree, bordering Oak between Masonic and Central. It’s still there, and many more have been planted throughout the panhandle to serve as border trees.

The black walnut, off Oak between Clayton and Cole was not only still present, but seems to be flourishing. It’s gloriously big with spreading branches and slim pale green leaves.

And, the one McClintock called the “big tree,” the giant sequoia, was still holding its own near the William McKinley monument. It was smaller than I expected, given the giants to be found in places like Sequoia National Forest. Then again, those trees have been growing for centuries. Assuming it was planted by Hall, at 153 years old, this one is still a baby.

+++

Here are the other tree maps from McClintock’s book in case you want to check on the trees there:

I used to live at Cole and Page. I always loved strolling through the Panhandle. Thanks for bringing back some great memories.

I like seeing people practicing tai chi in the pan handle…