What's in a name?

Last winter I came across a laminated newspaper article that was stapled to a park bench. “Old City Employee Stricken in Park,’ read the headline. It was an obituary from a 1912 issue of the San Francisco Examiner for a man named Patrick Quigley, a construction foreman in Golden Gate Park who “Turned Sand Dunes into Beauty Spot.”

I started spotting the same news clipping taped to lamp posts and utility poles all around the park. All had a QR code at the bottom and when I scanned it, I discovered they’d been put up by one Angus Macfarlane, a retired juvenile probation officer and amateur historian who was running an idiosyncratic one-man campaign to rename Stow Lake after Quigley.

Who’s Quigley? you might ask.

Well, that’s exactly Macfarlane’s point. Quigley was one of the laborers who literally built the lake 130 years ago—the sort of person who is rarely commemorated in public spaces.

Most of the landmarks in the park are named for rich and famous benefactors: the De Young museum, (for newspaper publisher Michael DeYoung); Spreckels Lake, (for sugar baron and park commissioner Adolph Spreckels); the Sharon building (for banker and former senator William Sharon), to name a few, (pun intended). Wealth and power confer naming rights then, as now. (See the Lisa & Douglas Goldman Tennis Center.)

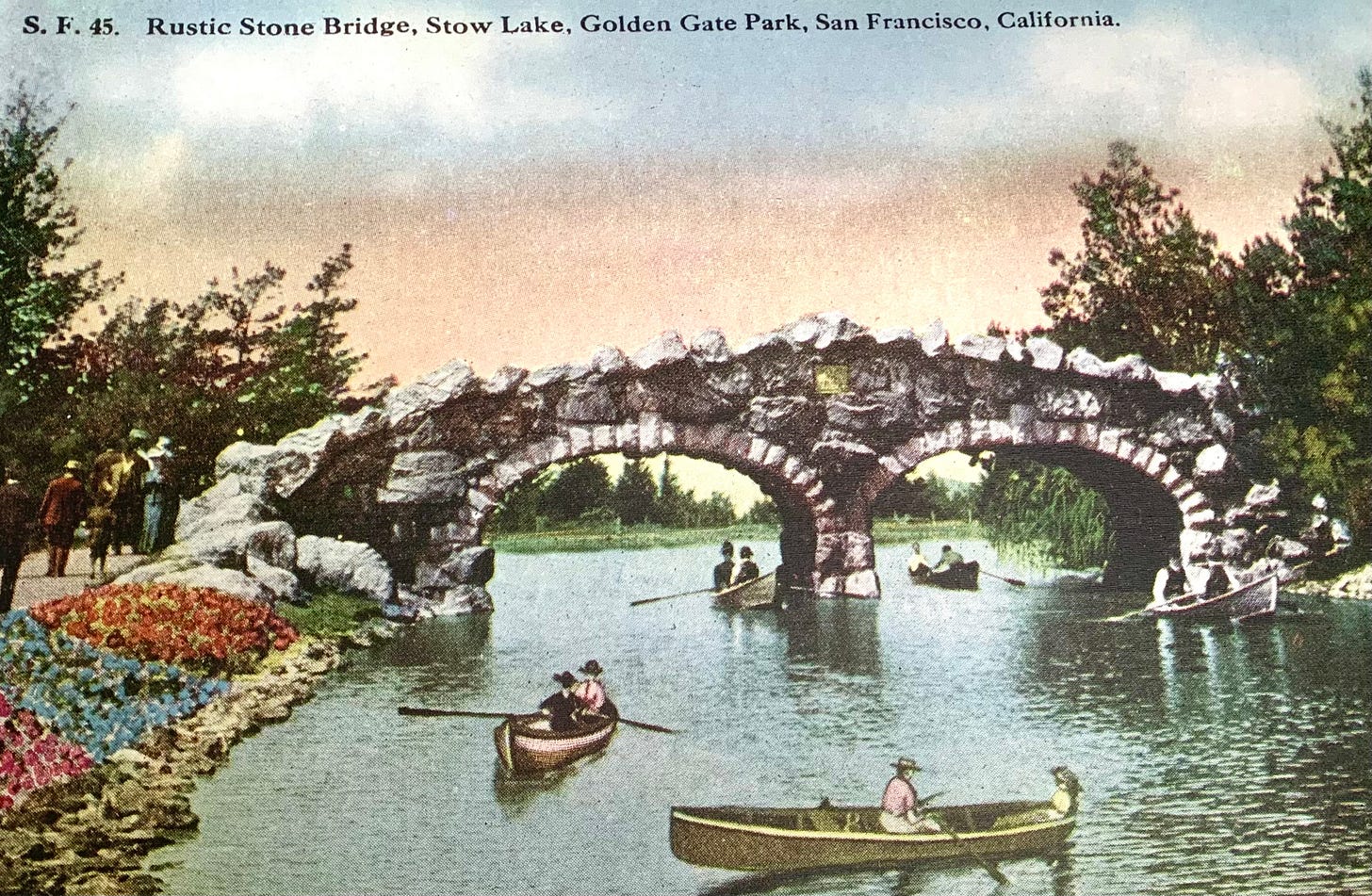

Every name carries baggage, but the namesake of Stow Lake is a particularly toxic sack. Stow was a Gold Rush-era politician, one-time speaker of the state Assembly and a lobbyist for the Big Four railroads. As a devoted member of what was then called the Board of Park Commissioners, he persuaded railroad baron Collis Huntington to donate $25,000 to create a waterfall that would tumble down the bare side of Strawberry Hill and empty into a reservoir at the base of the hill. (That cascade would be named – surprise, surprise – Huntington Falls.) The reservoir was extended to circle the hill, the waterfall was built and in 1893, the place was christened Stow Lake. Stow died suddenly two years later.

The name was unquestioned until a few years ago when San Francisco attorney Steve Miller learned about and began publicizing Stow’s noxious political views. Turns out Stow was a vicious antisemite and xenophobe who more than once expressed a desire to drive Jews out of California. He called for a “Jew tax” with that aim in mind. Rediscovery of that background sparked a drive to remove his name from the lake, as well as the boathouse and the surrounding drive. It’s been a slow process, but last week, the Board of Supervisors approved a resolution calling on the Recreation and Park Commission to come up with a new name.

When Macfarlane first heard about the push to rename the lake, he decided at once to nominate Quigley as the new namesake. He’d come across the man years before in one of his various deep dives into San Francisco history.

Though he has no formal training as an historian, Macfarlane is a dogged researcher. He loves the digging through public records and old directories, the burrowing through old newspapers, the dredging up of the past into present day light. For instance, a few weeks ago, we got together at Stow Lake and he said he had something to show me. We trudged to the top of Strawberry Hill where he gestured to a thicket of leaves and bramble. I pulled away the branches to find a dedicatory stone for Huntington Falls. I’d walked past that spot thousands of times but never noticed the stone before. Macfarlane reached into his backpack and pulled out clippers and a neon-yellow safety vest so he wouldn’t look “so outlawy.” He began clipping away the branches until the stone and its inscription were visible.

He discovered Quigley while excavating the history of the Little Shamrock bar on Lincoln Way, the city’s second oldest bar. He learned it was owned by the wife of a J.P. Quigley, whose father worked in the park. With assiduous digging, he slowly put together the story – or a story -- of the elder Quigley’s life. (He first shared it in the fantastic Outside Lands podcast.)

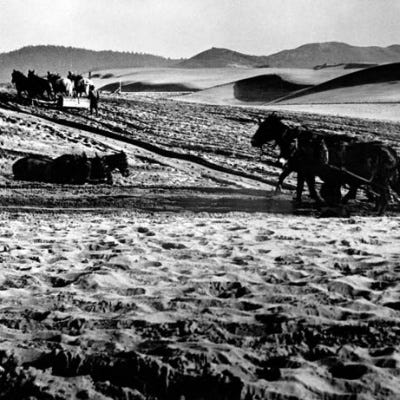

Quigley was born in Ireland and emigrated with his wife to the US in 1848, settling first in Mariposa County before coming to San Francisco. He was hired in 1871 or 1872 to start work on the park in what was then the daunting landscape of the Outside Lands, where every day was a battle with sand and fog and wind. The park was little more than a dream and a blueprint. At the time, only the panhandle was under construction and William Hammond Hall had yet to figure out how to control the dunes. Quigley was one of just 35 employees.

He came in as a laborer and in 1873 won promotion to be head of the teamsters, supervising the workers driving teams of horses and mules. He was one of the “pick and shovel guys” says Macfarlane, the manual workers who made real the visions of Hall and, later, John McLaren. They were the guys moving thousands of tons of dirt and rock and sand, leveling the hills, carving out valleys, laying down miles of macadam roads, spreading the daily loads of manure collected from the city streets that was used to grow the tens of thousands of trees.

“It was the same technology used to build the pyramids, man and beast. So, it was picks and shovels and wheelbarrows. You know, sweaty men and blistered hands. That’s how the work was done,” says Macfarlane. They worked nine hours a day, six days a week. A bell tower near what is now McLaren Lodge sounded the beginning and end of the day.

These were still wild days in the Outside Lands. Quigley joined Hall in a series of gun battles to oust squatters who were refusing to leave the site nearby slated to become Buena Vista Park.

Quigley may have been a grunt but he was an important grunt —so much so that the Park Commission gave him a house within the park’s boundaries. It was in the southeast corner, in what is now the triangle next to Kezar Stadium “so he could be on the job site,” says Macfarlane. The only other people allowed to live in the park were the night watchman and the superintendent. Quigley and his wife Mary raised nine children in the small cottage. Their nearest neighbors were a dynamite factory, and further away, a scattering of taverns, the Alms House and a hog ranch. “It was like a pioneer existence on the fringe of San Francisco, where the city meets the sand,” said Macfarlane.

Quigley worked in the park for 42 years. His obituary suggests he was still on the job when he suffered an injury that led to his death at the age of 83, on November 12, 1912. By then the park had reached its boundaries and he’d had a hand in much of its construction. Or as the obituary put it, “under whose direction all the great improvements and works were accomplished,” including Stow Lake, the Stadium (now the Polo Fields), and the Great Highway. As a token of appreciation for decades of service, the Park Commission awarded his family a paycheck for the remainder of the month of November. Two extra weeks of pay — and eventually, an eviction notice. With Quigley gone and his wife dead, his adult children had to leave the cottage in the park.

“Well, he deserves more than that,” says MacFarlane. “What he did is beyond being prominent or being a benefactor. He's a creator. He's the creator of Golden Gate Park, literally and figuratively. He deserves recognition for his work.” Quigley Lake might sound strange at first, he adds. “But I’m sure I could get used to it “

I confess I’m ambivalent about putting another person’s name on the site. Naming it for Great Blue Herons who nest there, or for Strawberry Hill or some other non-human feature could be less problematic. Birds and plants don’t come with baggage. There are such scant details in the record about Quigley, who knows who he really was. Then again, what we do know is that for 42 years he worked hard six days a week, nine hours a day to create a place of exquisite grace and beauty. Maybe that’s not such a bad thing to honor.

If you have thoughts about what the new name should be, contact the Recreation and Park Commission. It will also be holding three public hearings on the name change, starting with a community meeting on Zoom on June 1 and another on June 8 at the SF County Fair Building (Hall of Flowers).

An amazing story about a beautiful park built in the sand dunes by a crew led by Patrick Quigley. Of course he should be memorialized. Renaming Stow Lake is a great start. Angus Macfarlane is a true historian.

Great read, succinctly explained. Quigley Lake may seem odd at first, but for someone who dedicated over half his life to a thing that hundreds of thousands, if not millions of people enjoy today, that sits well with me.