I’ve been trying to write about play for the last two days — and it’s been surprisingly hard to do, which is more commentary on my life and these troubled times than the subject itself. Play flows out of a kind of mysterious alchemy that gets harder and harder to access as we age. One of the foremost “play advocates” the late Joe Frost writes, “the best play spaces have magical qualities that transcend the here and now, the humdrum and the typical..They’re permeated with awe and wonder.” Those words could apply across Golden Gate Park. Yet within this 1,000-plus acres of play-ground, children’s play (and I don’t mean sport) is mostly channeled into designated playgrounds.

This goes back to the park’s first decades, with the creation of the Sharon’s Children’s Quarter, one of the earliest public playgrounds in the country. The first specific play spaces for children were sand gardens, literally just heaps of sand, placed in the yards of the Boston Children’s Mission in 1885 at the behest of Dr. Marie Zakrzewska, who had seen children in Berlin delightedly playing outside in sand piles.

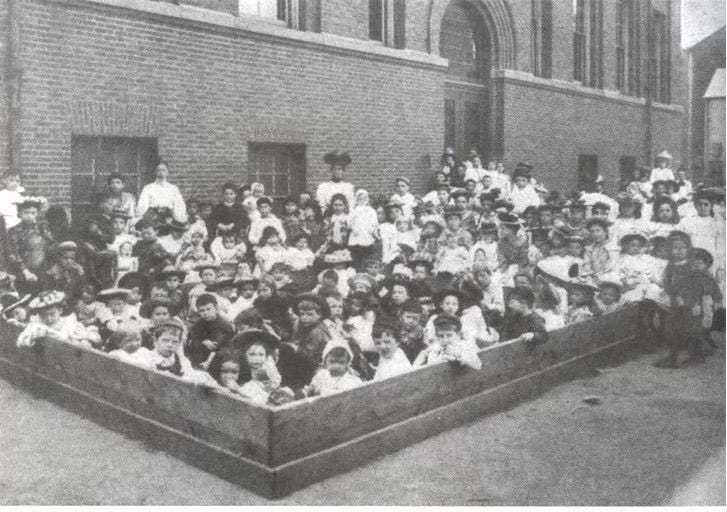

Yikes! that photo makes a sand garden look grim. But I have to believe were they not packed like sardines, those kids would have been having a great time. The idea of giving kids a space to muck about in sand helped inspire the playground movement that took off over the next few decades. This humble beginning is a good reminder of how little it takes to spark the joy of play.

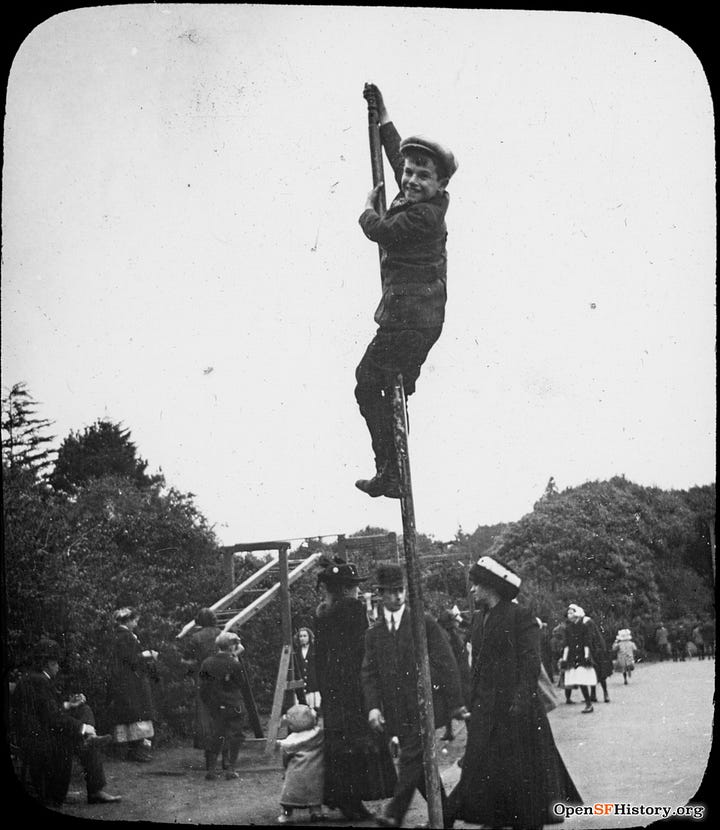

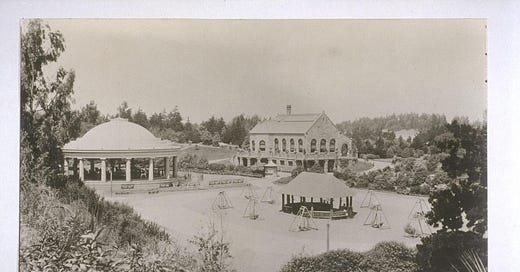

Let’s take a look at how this play space evolved. The Children’s Quarter opened on Dec. 22, 1888, funded through a $50,000 bequest left by robber baron William Sharon. It was designed, “to encourage virtue through organized play,” according to terence Young’s excellent history, “Building San Francisco’s Park, 1850-1930. In place of unsupervised play on dangerous city streets, the playground would provide a place of “healthful recreations,” as the program for the opening day festivities described it. It would provide directed opportunities, overseen by adults.

By today’s standards, the early grounds were fairly sparse: there were a handful of gondola swings, see-saws, slides, a maypole, and a baseball field for boys and a croquet court for girls. (I believe the slides were also sex-segregated.) There was also an early version of the carousel, this one under a canvas awning and with half the horses equipped with side saddles for the girls.

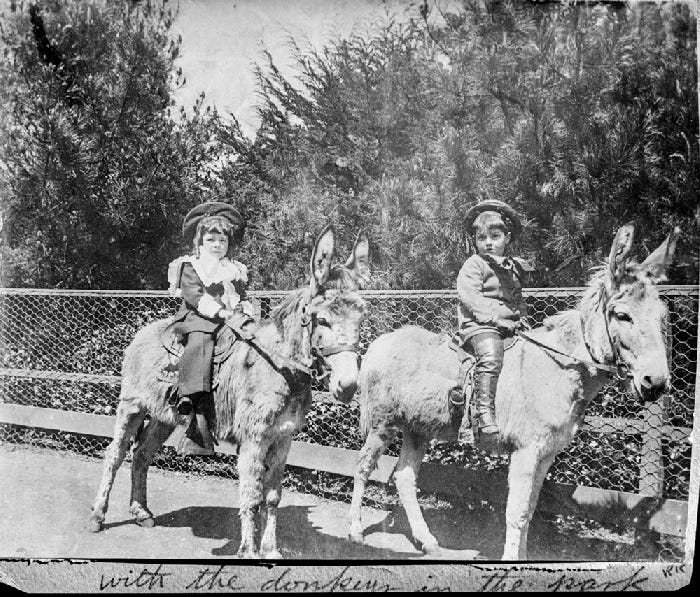

Milk and bread, coffee and ice cream could be had in the nearby Sharon Building, which also housed bicycles and tricycles for borrowing. Over the next few years, the merry-go-round got a permanent roof, a skating and bicycling rink were installed and donkey and goat cart rides were introduced.

One Los Angeles Times writer gushed about the scene in 1889: “What a crowd of happy little folks I found there! What an army of donkeys for them to ride! What a lot of Billy goats harnessed to pretty little carts. And what lots and lots of tricycles were being propelled over the wide sandy space set aside for their riders…Well, there was not a boy or girl among them all but looked glad to be alive, glad that they had that beautiful playground, where they could come and enjoy all these pleasures, with the trees, the flowers, the twinkling fountains and all the lovely things about them there.”

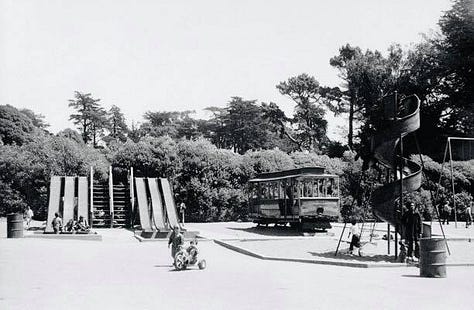

Through the years, more and more of the playground was taken up by equipment — new kinds of slides, swings, climbing structures. These photos tell part of of the story:

In 1943, a mini farmyard was installed “for enjoyment and to teach the fundamentals of farming and livestock handing,” as the “Chronicle” explained. It wasn’t clear how city children would put these teachings to use, still the barnyard was hugely popular. It held goats, chickens, ducks, rabbits, as well as a Holstein cow named Margo and her calves. Lessons in farm life continued a few years later when the playground was also planted with a Victory Garden.

I don’t know when the barnyard was dismantled, but by the time I started visiting the playground with my kids in the 1990s, the animals were long gone. In our era, the two biggest features of the playground were the weird origami-like modular climbing structure — where kids could disappear deep into its fractal bowels — and the famed cement slides. With the right piece of cardboard under her butt, a kid could shoot down those 75-foot slides. They were scary in the best kind of way — offering a taste of risk, like a roller coaster, without being truly dangerous (though scraped arms or knees occurred). My kids could spend a whole afternoon going up and down those slides.

In 2007, the playground got another facelift, with a design intended to reflect San Francisco’s natural landscape. Here’s how MIG, the design firm behind the $3.8 million renovation, describes the new space:

“Now, a boulder-lined stream bubbles along in the midst of hillside lookouts and meanders through a tree house village. Children can dig for artifacts in a large sand zone while others can sway on oversized cattails in the wetland zone..Across a plaza of trees and curving seat walls is the seaside environment, where aquatic forms created by artists Vicki Saulls and Scott Peterson inspire active and imaginative play. Sea caves enclose another sand area with climbable creatures like hermit crabs and sea turtles. Tactile tide pools and playful water jets erupt from sculpted sea lions. Two large climbing walls in the form of cresting waves provide a physical challenge that is safe for children of all ages and abilities.”

The beloved cement slides don’t quite fit into this pseudo naturalistic landscape, but the designers wisely maintained them.

It’s unquestionably a beautiful playground, filled with many opportunities for magic to strike. Yet, it also exists in its own firmly bounded world, separate from the rest of the park. To be sure, if you’re with a young child, you want that sense of safe enclosure. Still…

I keep thinking about something my eldest son, who’s now 34, said when I asked him about his favorite playground experiences in the park. He brought up the playground at Mother’s Meadow, one of the ones we visited most frequently. He didn't have any feelings about the swings or slides or monkey bars. No, it was the dense hillside of trees behind the playground that sticks in his memory — which to a kid loomed as long and large, and maybe as slightly scary, as a genuine forest. That’s where he and friends like to spend their playground time, playing amidst those trees, hiding, hunting, spinning out their own entertainments.

++

Postscript

Though Koret Playground gets the most attention, there are actually five playgrounds in the park. I spent an afternoon making the rounds of them all and here’s a brief rundown of the other four:

Ohhhh, I may love this newsletter most of all. (Besides the stellar writing, the photo of the kids packed "like sardines" into that sandbox was hilarious.) You got to the heart of what makes play actually joyful, and your now adult son nailed it, and youbrought it to light, that all of the people-made structures in the world can thrill, but it's wild nature that kids love the most. I remember a highly organized birthday party for my son at Stern Grove. All the treasures hunts and pin-the-tails went out the window when the kids wandered into the woods to stare for two hours at the giant banana slugs.

Oh and playground safety has some interesting angles. I used to write about this in the 1990s (when our kids were young) using people from this Iowa group. Source: National Program for Playground Safety

https://search.app/7YLCEaH3dMexr5X6A